“By Faith All Things Are Fulfilled”

- CFMCorner

- Nov 22, 2024

- 29 min read

Updated: Nov 27, 2024

Videos, Podcasts, & Weekly Lesson Material

Media | Lesson Extension |

|---|---|

Scripture Central | Ether 12–15 |

Follow Him | |

Line Upon Line | |

Teaching with Power | |

Don't Miss This | |

Book of Mormon Matters with John W. Welch and Lynne Hilton Wilson | |

Unshaken | |

The Interpreter Foundation | |

Scripture Gems | |

Come Follow Up | |

The Scriptures Are Real | |

Latter Day Kids | Ether 12–15 |

Scripture Explorers | Ether 12–15 |

Ether 12–15 | |

Talking Scripture | |

Saving Talents: Devotionals & FHE for Children | |

Grounded with Barbara Morgan | |

Our Mothers Knew It | |

Ether 12–15 The Rise & Fall of the Jaredites |

Resources and Insights for this Week's Lesson

The Book of Mormon: A Cultural and Religious Exploration

If you haven't already, review the materials that were covered in last week's lesson. I posted these latter than I usually do because I took some time off to spend with my new grand-baby. However, the materials shared last week are pretty insightful and they provide an excellent foundation for the topics that we explore in this week's lesson.

This week's material brings us to a profound moment in history where prophets and scribes—Mormon, Moroni, and Ether—stand as witnesses to the complete and tragic destruction of their people, which included much of their knowledge, and culture.

As keepers and scribes of the sacred records, their divine commission was to preserve the word of God and the story of their people with absolute fidelity. Even as their own communities fell into chaos and would not hearken to their words, these faithful scribes placed their trust in the Lord's promises. They knew that their efforts would not be in vain, as their records would one day "cry from the dust" to guide and testify to God's people in the Latter Days.

Reading these passages through the lens of scribes and record keepers invites us to draw parallels to other faithful Jewish scribes throughout history, who also sacrificed greatly to protect and preserve their sacred writings.

For example, the Essene scribes of Qumran hid their records in desert caves to protect them from the Roman armies that decimated Jerusalem in 70 AD. Rediscovered in 1945, these records, known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, have provided invaluable insights into history, culture, and theology, filling critical gaps in our understanding.

Similarly, the Masoretes of Tiberias in the 6th century AD faced the daunting task of preserving their language and traditions amidst intense persecution. As the Hebrew language fell into obscurity and the sacred records were intentionally being destroyed in wars and systematic acts of violence, fewer people were able to access, let alone read these ancient texts.

The Masoretes, deeply committed to preserving their language and culture, shared concerns similar to those expressed by Jared and his brother. Recognizing the urgency and gravity of their mission, they developed a system to safeguard their pronunciation and cantillation traditions. This system was designed not only to preserve the oral traditions that had been passed down for centuries but also to create a bridge between the established past and an uncertain future.

In addition to preserving these musical and linguistic traditions, the Masoretes sought to codify and standardize the various systems and records that were already circulating. By doing so, they aimed to streamline their records, to ensure the highest level of accuracy while maintaining the integrity of their sacred texts for generations to come.

Like Mormon, Moroni, and Ether, these scribes understood that time was running out. They recognized the need to act swiftly to prevent their language and traditions from falling into extinction, as had previously occurred with other ancient cultures, such as with the Egyptian Hieroglyphs. The Masoretes painstaking efforts ensured that the word of God and the cultural heritage it carried would endure, testifying of their diligent faith and dedication.

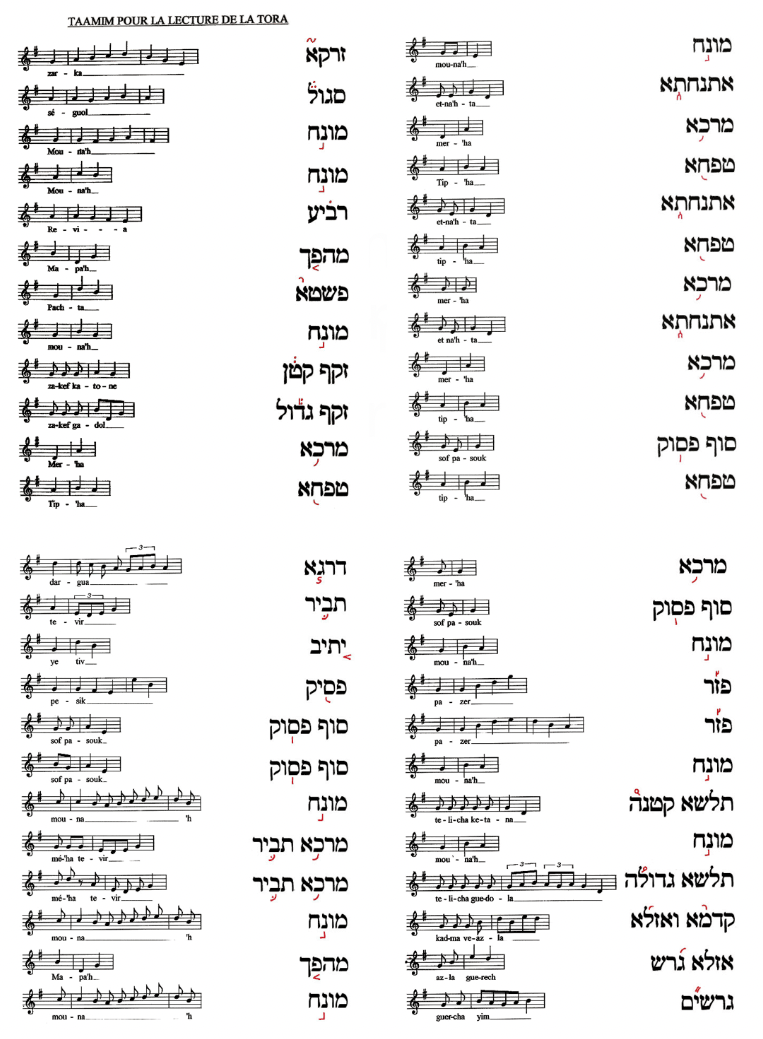

With this recognition in mind, the scribes carefully developed the Niqqud and the Ta'amai HaMikra: a series of diacritic dots, dashes, and notation devices that helped the reader to learn and remember how to pronounce and chant the text, in accordance with their earlier traditions.

Niqqud:

The Niqqud system was developed to indicate vowel sounds, addressing a key limitation of Hebrew's abjad script, which identified letters only as consonants. This contrasts with the Greek Alphabet, which developed later and served as the basis for the Latin alphabet, where specific letters were modified to represent vowel sounds. However, the Greek-inspired system was unsuitable for the Masoretes' purposes.

The Masoretes were not only concerned with accurate pronunciation but also deeply committed to preserving the memory and readability of the original texts. Rather than completely altering the abjad, as the gentile Greeks did with their script, the Masoretes devised a system that placed vowel markings below and around the original consonant letters. This approach preserved the integrity of the ancient texts while creating a bridge between the old script and the evolving needs of future readers.

In many ways, these diacritical marks functioned like training wheels, helping developing readers to learn the language while maintaining a connection to the ancient tradition. As readers gained proficiency in the language and its grammatical rules, they would naturally learn which vowels to use, when to use them, and how to interpret them. Once students achieved fluency, they would become less reliant on the Niqqud.

The Ta'amai HaMikrah (cantillation symbols or trope) functioned in a similar way to the Niqqud and served multiple functions and purposes. These symbols not only guided the reader on how to chant the text according to the oral traditions, but they also acted as a form of punctuation.

For instance, specific tropes indicated natural pauses and cadences in the text, helping both the reader and the listener understand the structure and flow of a passage. Examples include the the ֑ Etnachtah, which functions like a comma, the : Zaqef Qaton, similar to a colon, and the | Sof Passuk, which acts as a period. These symbols enhanced both the readability and the musicality of the text, making it easier to understand, interpret, and convey the sacred writings with precision.

We can see some of these symbols used in the following example from Genesis 1:1, which reads from right to left, Bereshit bara Elohim, et HaShemayim ve'et HaEretz. "In a (not the) beginning created God (etnachta, pause), (behold) the heavens and the earth (zaqef qaton).

In this example, the highlighted yellow symbols are the Ta'amai HaMikrah (trope), while the black dots, dashes, and markings indicate the Niqqud (vowel points) along with the Hebrew consonants. Notice that each word has a trope symbol, as is the case throughout the Old Testament. For instance, the Etnachta appears under the word "Elohim," functioning as a pause or half cadence, dividing the verse into two parts. Similarly, at the end of the phrase, following "HaEretz" ("the earth"), we see a Zaqef Qaton, which acts like a colon. This invites the reader to reflect on or anticipate the subsequent elements of God's creation, which are organized into the seven creative periods listed in the description that followed.

These markings effectively preserved what we now recognize as punctuation. Just as proper punctuation is essential in modern languages, the Ta'amai HaMikrah ensured the accurate interpretation and retention of the intended meaning of the text. A humorous yet well-known example in English illustrates the importance of punctuation: "Let's eat, Grandma" versus "Let's eat Grandma!" While the words are identical, the punctuation radically changes the meaning. Similarly, the Ta'amai HaMikrah provided crucial interpretative guidance, ensuring the text was read, understood, and transmitted correctly according to tradition.

Just for fun and as an additional resource, below is a compilation of the Ta'amim along with their associated symbols and melodies. It’s fascinating to note that while the melodies differ across various Jewish traditions—such as Ashkenazic, Sephardic, and Yemenite—all communities use the same Masoretic symbols.

The Masoretes' Legacy and the Power of Chanting

The Masoretes preserved and continued their legacy by systematizing the Niqqud and Ta'amim HaMikrah. These symbols not only preserved pronunciation and musical traditions but they also enhanced the accuracy and retention of scripture.

Chanting, central to Torah education in both modern and ancient times, was emphasized by scholars like Rabbi Akiva (ca. 50–135 CE). In a third-century Talmudic discussion of Nehemiah 8:8, Rabbi Akiva connected Second Temple musical practices, as specified by the text, "gave the sense," to the melodic cadences of the Ta'amim "tastes." Similarly, Johanan of the Masoretic Tiberias Academy (279 CE) declared that "whoever reads [the Torah] without melody and studies [Mishnah] without song, to him may be applied the verse: ‘Moreover, I gave them laws that were not good and rules by which they could not live’" (Ezekiel 20:25). This underscores the Jewish belief that music was not merely an embellishment but an essential part of understanding and living the law of God.

Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, cantor and author of Jewish Music, and It's Historical Development points out that even Jesus Christ utilized an early form of these cantillation practices, particularly when he stood before the synagogue in Nazareth, as specified in Luke 4:16. "And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up: and, as his custom was, he went into the synagogue on the sabbath day, and stood up for to read." Idelsohn explains that the custom that is being referred to in this chapter is the cantillation practices that were part of Jewish tradition, as anytime the Torah is publicly read before a Jewish congregation, it was always meant to be chanted.

Trope in the Ancient World

The traditions of music and cantillation held immense importance to the ancient world, and not only among the Israelites. In Psalm 137, we read that following the Babylonian invasion, the musicians hung their harps upon the willows while their captors pressed them to divulge their musical traditions, but the Jews refused to do so, knowing that this sacred knowledge would be used against them.

Ancient civilizations did not view music as we do today, simply as a means of entertainment. For them, music was a powerful means of divine communication and education. Music was the primary method by which they learned and preserved scripture. We must remember, that written records during this time were scarce and prohibitively expensive, as each word had to be painstakingly copied by hand. Additionally, the materials used for these records, such as vellum, were costly—requiring, for instance, the hides of approximately 65 large kosher animals for a single Torah scroll. Other materials, such as metal plates used by some Jewish (copper scolls) and Book of Mormon scribes, added further expense and effort.

The Role of Music in Preservation and Education

Music was essential for retention and accessibility. Priests and scribes began their training in the Torah from an early age, much like Moroni did in the Book of Mormon. They would sometimes have to leave their families, to live in communities dedicated to learning both the written and oral traditions—just as Hannah’s son, Samuel, studied under Eli. These young students were tasked with memorizing the entire Torah, in addition to the rest of the Tanakh, which they achieved through the use of musical mnemonic traditions.

The Levite priests, in particular, were responsible for committing the Tanakh to memory. They would travel between communities to teach it orally, as the written records were safeguarded in the Tabernacle and Temple treasuries. These Levites, sometimes referred to as Shirath (translated as "servant" or "minister"), essentially acted as wandering minstrels, (ministers of El "God") a tradition that would later inspire the famous troubadours of France, following the crusades. (The word troubadours was, in fact, derived from the same Greek word "tropus," the Greek nickname used to describe the Ta'amim, which was also a term adopted by the Jews. Although, the French term was passed down through different channels, migrating through the Occitan and Latin tropare.)

Likewise, the Hebrew root of the word Shirath can be linked to the word Shir (meaning "song"). This highlights the Levite's role as both keepers of scripture and stewards of musical tradition. After all, these were the priests that David assigned to be the song leaders of the Temple (1 Chronicles 6:31), based upon their previous responsibilities as the protectors of the Ark of the Covenant (Numbers 4, Deut 31:9-13,19-22).

Another term used to describe these Levite officers was zamar or zimri, derived from the Hebrew verb זמר (Zayin-Mem-Resh), which also carries connotations of singing and musical service. In earlier lessons, we discussed the likelihood that Zoram may have served in such a capacity. He was described as a "servant" and caretaker of the temple archives, a role traditionally associated with the Levites.

Interestingly, Zoram's descendants, the Zoramites, later claimed that Zoram had been unjustly deprived of his rightful privileges as the leader of Lehi's posterity. This claim, as recorded in Alma 54:23, was a distorted form of propaganda designed to justify the Zoramite's rebellion and it was intended to strengthen the political aspirations of the kingmen. Despite their prideful assertions, this manipulation sadly underscored their departure from the humility and faithfulness exemplified by Zoram, their ancestor, altogether ignoring the close relationship that existed between him, Nephi, and their families, which ultimately intermarried and blended together as one.

The Levites' Multifaceted Role: Music, Teaching, and Warfare

The Levites’ duties extended beyond teaching and preserving scripture. They often served in military capacities, as did the Levite protectors of the Ark of the Covenant. Music played a crucial role in their success on the battlefield and in protecting the Ark. It served as a means of communication in an era that did not have modern technology, such as radios and cell phones. Instruments like the shofar and drums could be used to relay warnings and tactical commands over long distances, much like Morse code, which was introduced in the early 19th century.

Several scriptural accounts illustrate this practice of combining music, leadership, and military strategy. Examples include generals such as Jehu (2 Kings 9:1-13,31) and Gideon (Judges 6-7), the Chief Musicians of the Psalms, and the iconic story of the trumpets of Jericho, whose blasts caused the walls of the city to come tumbling down (Joshua 6).

Similarly, the Book of Mormon references similar accounts, with examples like Mormon and Moroni, who served as both scribes and military leaders. We also observe echos of this practice with Captain Moroni, and his rivals Ammoron and Ammalikiah, who strategically enlisted the Zoramites to serve as captains of the Lamanite armies. While the Zoramites had become prideful and rebellions, they were also very educated, highly skilled in musical and scribal traditions. Additionally, their expertise in military fortification strategies significantly bolstered the strength and capability of the Lamanite forces. We can see remnants of this in Ether 14:28, when Coriantumr sounded a trumpet to invite Shiz's armies to battle.

As we can see from these examples, the properties of music and sound are profound and multifaceted, reaching far beyond the scope of what can be included in this lesson.

Now, Let's bring this back to the Book of Mormon and the account of Moroni. In Ether13, Moroni laments because of the weakness of his writing, saying "Lord, the Gentiles will mock at these things, because of our weakness in writing; for Lord thou hast made us mighty in word by faith, but thou hast not made us mighty in writing..."

He then goes on to describe how the Jaredites had a more advanced writing system, explaining that over time the Nephite writing system had degenerated, expressing that, "when we write we behold our weakness, and stumble because of the placing of our words; and I fear lest the Gentiles shall mock at our words."

The Lord replied, "Fools mock, but they shall mourn; and my grace is sufficient for the meek, that they shall take no advantage of your weakness; And if men come unto me I will show unto them their weakness. I give unto men weakness that they may be humble; and my grace is sufficient for all men that humble themselves before me; for if they humble themselves before me, and have faith in me, then will I make weak things become strong unto them. Behold, I will show unto the Gentiles their weakness, and I will show unto them that faith, hope and charity bringeth unto me—the fountain of all righteousness."

As we consider the history of the Jews and the Gentiles, including the complexity of their writing systems, we begin to get a deeper glimpse into the profound nature of these prophesies. We begin to recognize how things as small and simple as the letters and diacritical markings, the "Jots" (Yods, the smallest, and tenth letter of the Hebrew Alphabet), and "Tittles" (the diacritic markings) of the Law, create the building blocks of the word. And these things did indeed bring great things to pass, including the fulfillment of the promises made to prophets like Nephi, Alma, and Helaman, when they were instructed to keep a record of their people. When passing the records down to Helaman, Alma explained to his son,

"For it is for a wise purpose that they (the records) are kept. And these plates of brass, which contain these engravings, which have the records of the holy scriptures upon them...it has been prophesied by our fathers, that they should be kept and handed down from one generation to another, and be kept and preserved by the hand of the Lord until they should go forth unto every nation, kindred, tongue, and people, that they shall know of the mysteries contained thereon... Now ye may suppose that this is foolishness in me; but behold I say unto you, that by small and simple things are great things brought to pass; and small means in many instances doth confound the wise. And the Lord God doth work by means to bring about his great and eternal purposes; and by very small means the Lord doth confound the wise and bringeth about the salvation of many souls. And now, it has hitherto been wisdom in God that these things should be preserved; for behold, they have enlarged the memory of this people, yea, and convinced many of the error of their ways, and brought them to the knowledge of their God unto the salvation of their souls. Yea, I say unto you, were it not for these things that these records do contain, which are on these plates, Ammon and his brethren could not have convinced so many thousands of the Lamanites of the incorrect tradition of their fathers; yea, these records and their words brought them unto repentance; that is, they brought them to the knowledge of the Lord their God, and to rejoice in Jesus Christ their Redeemer. Now these mysteries are not yet fully made known unto me; therefore I shall forbear. And it may suffice if I only say they are preserved for a wise purpose, which purpose is known unto God; for he doth counsel in wisdom over all his works, and his paths are straight, and his course is one eternal round."

In preparing this lesson, I debated about including these insights, which are a part of a broader project that I am currently working on. However, as I kept working on this lesson, these concepts were all I could think about, because they perfectly depict the situations that we see unfolding in the closing chapters of Ether and Moroni. These accounts demonstrate one of the many ways in which we can see the hand of the Lord at work, in fulfilling His promises to His people in mysterious and miraculous ways. I believe that these principles were understood and intentionally preserved by Ether and Moroni, as they served an important part in the "Restoration of all things," which are now only beginning to come to light, thanks to the diligent efforts of the Jews and the remnants of Joseph, in their faithful efforts to serve their God.

Additional Resources:

Hugh Nibley's Honors Book of Mormon Lectures 1988-1990 (Lecture 110)

Come, Follow Me Study and Teaching Helps — Lesson 46: Ether 12-15

Audio Roundtable: Come, Follow Me Book of Mormon Lesson 46 (Ether 12-15)

“They Shall No More Be Confounded”: Moroni’s Wordplay on Joseph in Ether 13:1-13 and Moroni 10:31

Place of Crushing: The Literary Function of Heshlon in Ether 13:25-31

Scripture Roundtable: Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Lesson 46, “By Faith All Things Are Fulfilled”

Overview

Ether 12 is one of the most doctrinally rich chapters in the Book of Mormon, offering profound insights on faith, hope, and charity. Moroni, reflecting on Ether’s writings, expounds on the necessity of faith in enabling miracles, enduring trials, and receiving salvation. He provides examples of faith from Jaredite and Nephite history and addresses his own struggles with perceived weakness, finding reassurance in God’s grace. The chapter underscores themes of faith’s transformative power, the interconnectedness of hope and charity, and the Lord’s ability to turn human weakness into strength.

References and Cultural Contexts for Investigation, Contemplation, and Discussion:

Faith Precedes Miracles:

Faith is the foundation of spiritual growth and blessings. It requires belief in things not seen and a willingness to trust God’s timing and purposes.

Faith as a Test:

The principle that faith is tested before blessings or miracles aligns with ancient covenant traditions, where trust in God’s promises often required enduring adversity.

Faith, Hope, and Charity are Interconnected:

Faith inspires hope, a confident expectation of God’s promises. Hope leads to charity, the pure love of Christ, which is the crowning virtue of discipleship.

Weaknesses Invite God’s Grace:

Moroni’s struggle with his own inadequacies highlights the universal truth that humility and faith open the door for God’s transformative power.

Transformation Through Grace:

Moroni’s personal struggles reflect a universal truth: God uses human limitations to teach humility and reliance, a theme echoed in both biblical and Book of Mormon contexts.

Faith’s Role in Salvation:

Faith is essential for enduring trials, enabling miracles, and achieving eternal life. It connects believers to Christ, who is the source of all blessings.

Examples of Faith in Action:

The examples Moroni recounts demonstrate how faith has always been central to God’s interactions with His children, from the brother of Jared to Alma and Amulek.

Charity as the Pure Love of Christ:

Charity, or Christlike love, is the ultimate goal of faith and hope. It allows believers to emulate Christ and inherit eternal life.

Charity as the Greatest Virtue:

The emphasis on charity as the ultimate goal mirrors teachings in 1 Corinthians 13, reinforcing the universal and timeless nature of Christlike love.

Literary & Linguistic Observations:

Cultural, Archeological, and Geographical Insights:

Major Topics/ Themes | Cross-References, Videos & Resources |

|---|---|

Verses 1-5: Ether’s Call to Repentance & Faith | |

| |

Verse 6: Moroni's Explanation of Faith | |

Faith:

| Faith

|

Verses 7-9: Miracles Require Faith | |

| |

Verses 10-22: Examples of Faith in Action in accordance with the "Holy Order" of God. | Drawing the Power of Jesus Christ into Our Lives -Pres. Russell M Nelson |

Historical Examples of Faith:

| Qadosh (קָדוֹשׁ) – Holy

Seder (סֵדֶר) – Order

|

Verses 23-27: Moroni’s Personal Struggles with Weakness | |

| Weakness

Grace How Does Grace Help Us Overcome Weakness? |

Verses 28-34: Faith, Hope, and Charity | |

| Hope

Charity

|

Verses 35-41: Moroni’s Final Exhortation | |

|

Ether 13 highlights Ether’s prophecies concerning the New Jerusalem and the future destiny of the American continent. He declares that this land is a chosen land of inheritance for God’s covenant people and foresees the establishment of a New Jerusalem as part of the fulfillment of God’s promises. Ether also continues to warn the Jaredites of their impending destruction due to their wickedness, but his words are rejected. The chapter underscores themes of covenant lands, divine promises, repentance, and the consequences of rejecting prophecy.

References and Cultural Contexts for Investigation, Contemplation, and Discussion:

The New Jerusalem and Covenant Lands

Ether’s prophecy about the New Jerusalem aligns with the broader scriptural theme of covenant lands being places of refuge and spiritual renewal. The New Jerusalem represents a future gathering of God’s covenant people and the fulfillment of His promises.

The name Jerusalem (Yerushalayim) inherently implies two holy cities, as the -ayim suffix indicates a dual noun that comes in a pair.

Rejection of Prophets

Like other prophets in both the Bible and Book of Mormon, Ether is rejected and persecuted for delivering God’s warnings. His experience reflects the resistance often faced by those who call people to repentance.

Parallels to Biblical Prophets

Ether’s experience mirrors that of biblical prophets like Jeremiah and Isaiah, who warned of destruction and faced persecution for their messages. His rejection underscores the resistance often faced by those who deliver uncomfortable truths.

The Consequences of Wickedness

The chapter emphasizes the inevitability of divine judgment when warnings are ignored. Coriantumr’s fate serves as a poignant reminder of the consequences of pride and rebellion.

The Fulfillment of Prophecy

Ether’s specific prophecy that Coriantumr would survive to meet another people is fulfilled when he encounters the Mulekites (Omni 1:20-22). This precise fulfillment testifies of God’s power and the reliability of prophetic warnings.

The Hope of Redemption

Even amidst destruction, Ether’s prophecy of the New Jerusalem offers hope for a future of righteousness and divine fulfillment.

Literary and Linguistic Insights:

Major Topics/ Themes | Cross-References, Videos & Resources |

|---|---|

Verses 1-8: Prophecy of the New Jerusalem | |

| The New Jerusalem in Scripture

Covenant Lands

Hebrew word: יְרוּשָׁלַיִם (Yerushalayim) — “City of peace,” "The City Where Peace is (or will be) Taught/ Shown/ Seen"

|

Verses 9-12: Destruction of the Jaredites and inhabitants of Jerusalem Foretold and the Future of a new and Restored city | |

| |

Verses 13-22: Coriantumr and the Fulfillment of Prophecy | |

Ether prophesies directly to Coriantumr, warning that if he and his people do not repent, the entire Jaredite civilization will be destroyed. Coriantumr himself will be spared but will live to witness the annihilation of his people and encounter another people (fulfilled in Omni 1:20-22 when he meets the Mulekites).

| |

Verse 23-31: Shared defeats Coriantumr | |

|

Ether 14 details the spiraling descent of the Jaredite civilization into chaos, violence, and total destruction. Following Ether’s prophecy, the Jaredites engage in unrelenting warfare, driven by pride, vengeance, and greed. Coriantumr and various rivals vie for power, with the battles escalating in scale and brutality. This chapter underscores themes of pride, greed, and the devastating consequences of rejecting God’s warnings.

References and Cultural Contexts for Investigation, Contemplation, and Discussion:

Pride and Ambition Lead to Destruction

The Jaredites’ downfall is driven by pride and ambition, as rival leaders prioritize power over peace. This pride blinds them to the warnings of Ether and the possibility of repentance.

Greed as a Catalyst for War

Greed and the pursuit of wealth and power fuel the conflict, echoing themes from the Book of Mormon that warn against the love of riches (e.g., 1 Timothy 6:10).

The Consequences of Wickedness

The land itself becomes cursed, a recurring motif in scripture to signify the moral and spiritual degradation of a people. This reflects the principle that sin not only harms individuals but also affects society and the environment.

Cursed Land in Ancient Thought

The idea of a cursed land reflects biblical motifs where the environment suffers as a consequence of human wickedness. In Ether 14, the desolation of the Jaredite lands parallels other scriptural accounts, such as the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah or the curses pronounced in Deuteronomy 28.

Unrestrained Violence and Societal Collapse

The unrelenting warfare highlights the ultimate consequence of a civilization consumed by vengeance and greed: total collapse and desolation.

Cycles of Revenge and Violence

The unrelenting violence among the Jaredites reflects a destructive cycle of vengeance, a common theme in ancient societies where retaliation perpetuates conflict. This mirrors warnings in the Bible against vengeance, such as in Leviticus 19:18.

The Role of Prophets in Declining Societies

Like other prophets, Ether serves as a lone voice calling for repentance amidst widespread wickedness. His rejection and isolation reflect the pattern of prophets like Jeremiah, who warned of destruction but were ignored.

Linguistic and Literary Observations:

Cultural, Archeological, and Geographical Insights:

Major Topics/ Themes | Cross-References, Videos & Resources |

|---|---|

Verses 1-6: Prophecy Fulfilled and Chaos Unleashed | |

| Pride

Greed

|

Verses 7-10: Coriantumr’s Battle to regain Power | |

| Greed

|

Verses 11-17: Shiz Emerges as a Rival | |

| |

Verses 18-20: Widespread Division & Destruction | |

| Desolation

|

Verses 21-31: Unrelenting Violence | |

Armies Gather for Final Conflict:

| Sword

|

Ether 15 describes the final, catastrophic collapse of the Jaredite civilization. Despite Ether’s prophetic warnings, Coriantumr and Shiz lead their people into unrelenting warfare, driven by pride, vengeance, and ambition. The battles escalate in brutality and destruction until the entire Jaredite population is annihilated. Coriantumr alone survives, fulfilling Ether’s prophecy. This chapter underscores themes of divine judgment, the tragic consequences of ignoring prophetic warnings, and the self-destructive nature of pride and revenge.

References and Cultural Contexts for Investigation, Contemplation, and Discussion:

Pride and Vengeance as Catalysts for Destruction

The Jaredite civilization’s downfall is rooted in unrelenting pride and a refusal to seek reconciliation. Both Coriantumr and Shiz prioritize vengeance over peace, driving their people to total annihilation.

The Consequences of Ignoring Prophecy

Ether’s prophecy about the destruction of the Jaredites is fulfilled with exact precision, highlighting the certainty of divine judgment for those who reject God’s warnings.

Total Societal Collapse

The final battles draw in the entire Jaredite population, including non-combatants, signaling the complete breakdown of societal structure and values.

Isolation and Despair

Coriantumr’s survival as the lone Jaredite underscores the profound isolation and despair that result from prideful rebellion against God.

Ether and Mormon's Hope that God would fulfill his Promises

Cultural Architectural, and Geographical Insights:

Major Topics/ Themes | Cross-References, Videos & Resources |

|---|---|

Verses 1-6: Ether’s Prophecy and Coriantumr’s Realization | |

| Pride

Vengeance

|

Verses 4-10: Coriantumr’s Offer of Peace and Shiz’s Rejection | |

Coriantumr’s Surrender:

| |

Verses 12-18: Gathering of Armies for a Final Battle | |

| |

Verses 19-27: Complete Revocation of the Spirit and Days of Relentless Fighting | |

| |

Verses 28-30: The Final Combat | O, Remember, Remember - President Eyring |

The Last Combatants:

|

Church Videos & Resources

Scripture Central

Study Guide The study guide with the Reading Plan is now up under the Scripture Central Podcast Materials

BYU’s RSC

Comments